You can view the entire catalogue online here for free by clicking on view sample pages.

Introductory Essay

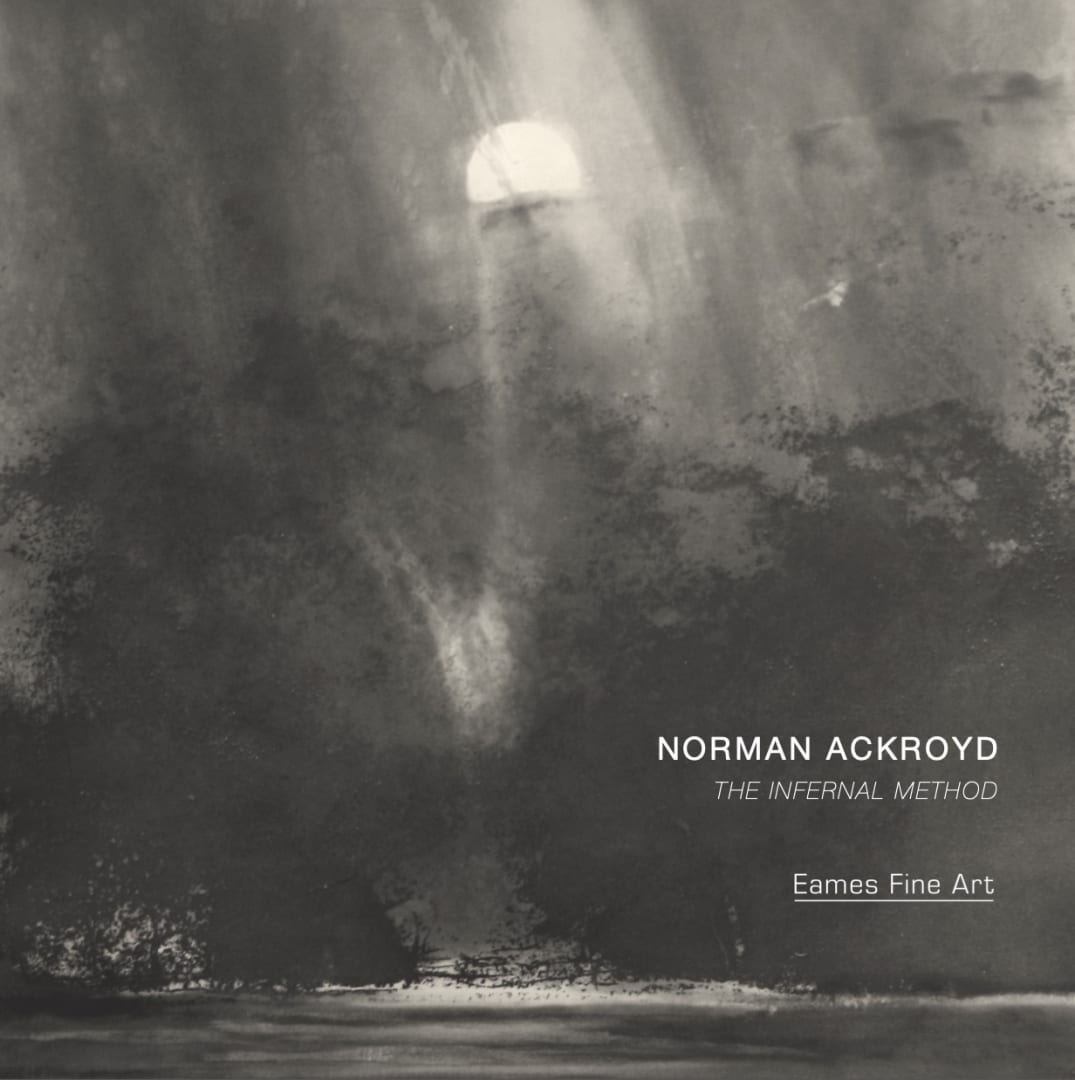

It is easy to reach for the imagery of alchemy to describe the printmaking process of etching, and descending into Norman Ackroyd's print studio, one is tempted to compare it to the laboratory of an alchemist. To someone who is not themselves a printmaker, the various techniques that Norman employs in his printmaking can seem esoteric: aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite. There are solutions to be mixed, some of which contain corrosive substances, and, of course, this is the site of a kind of transubstantiation of metals - not into gold, but certainly into images that are as equally refined as that most precious of elements.

However, it would be entirely inaccurate to characterise the man to whom this workshop belongs as a beard-stroking mystic. The last tannery closed just ten years before Norman established his studio here in Southwark in 1983, and the street names in the immediate vicinity (Tanner, Leathermarket, Morocco) still bear witness to the prevalence that industry once enjoyed in the area. Like a tannery, Norman's studio, ink-soaked and occupied by imposing machines which have remained essentially unchanged for half a millennium, is also a site of graft. There is a kind of paradox at play, which is fitting when one considers the artwork on display in The Infernal Method, especially the newer work, possessing as it does a delicacy quite at odds to the violence inherent not just in its subject matter, but in the very process by which it is produced.

The title of the exhibition comes from William Blake's Marriage of Heaven and Hell, in which the poet-artist pairs his own prints and philosophy to explore another paradoxical coupling, namely that of which Blake terms Reason (the domain of heaven) and Energy (belonging to hell). It is a concept at the very heart of Norman's own method.

For all his technical mastery and virtuosity in the handling of his materials, this method begins far from the studio, most usually in a boat, miles and miles from the mainland, whether that land be Ireland or the northern coast of Britain. It is the most remote parts of the United Kingdom, the islands and sea stacks that jut defiantly out of the Atlantic, that have occupied Norman's imagination for the best part of half a century, and to which he returns year after year.

One benefit of this continued interest is an encyclopaedic knowledge of these archipelagos. He can speak at length, for example, about St Kilda, to which the towering stacks of Stac an Armin and Stac Lee, which feature twice in the exhibition, belong. He speaks of it as a kind of utopia during the 4,000 years it was inhabited, too remote for money to have found it out, the United Kingdom's very own Galapagos, possessing its own species of tern and dormouse, a unique breed of sheep. Even the people, he says, evolved differently, with prehensile feet to facilitate climbing the stacks to harvest gannet chicks.

Then came the Victorian tourists, in their steamers, with their corrupting money, desirous, as Norman puts it, to see the heathens for themselves. It is a pertinent choice of word, for the utopian image he conjures up sits in stark contrast to many of the images he produces. The archipelagos are, after all, the result of volcanic activity, molten lava erupting up from below, eventually forming granite, a stone so solid even the roiling Atlantic cannot wash it away. To this day, when you approach them, with the gannets, six-foot in wingspan, screaming, shooting down out of the sky like arrows, and the stench, of the guano and the rotting fish, and the sea spray, there remains, he admits, something infernal to this part of the world.

Of course, some of these elements are by necessity not present in Norman's prints. It is not reality which we are being presented with; for all his extensive knowledge, Norman's work goes beyond the merely factual. It is for this reason that he studiously avoids using cameras, relying exclusively on the sketches and watercolours (examples of which are included in this exhibition) that he executes from the boat when he is before his subjects. Although it is not quite true to say that these notebooks, decades-worth of which sit in his studio, are his only resources. Just as the St Kildans evolved to suit their environment, Norman, too, has evolved, so that when he is producing these watercolours, he is not simply recording what he sees, as would a camera, rather he is creating a direct link between his subject and his artistic process, etching, as it were, the image into himself. Thus, even when not permitted to circumnavigate the islands, Norman is able to produce new work, as demonstrated by his most recent boxed set, work which is as full of vigour and atmosphere as anything he has hitherto produced.

Luke Wallis, August 2021